New Boston Coke was a former component of the Portsmouth Steel complex in New Boston, Ohio. Due to foreign competition and outdated technology, the integrated mill was closed in 1980 while the coke plant remained in operation until 2002.

History

The beginnings of the steel industry in New Boston began with the plotting of Portsmouth at the junction of the Scioto and Ohio rivers in 1803. 6 Subsequent discoveries of iron ore in the foothills of southern Ohio, along with vast virgin forests and the availability of two major rivers, led to the construction of numerous blast furnaces.

One of the first ironworks was the Portsmouth Iron Works, operated by Glover, Noel & Company, in 1831. 2 6 18 It consisted of a rolling and slitting mill in Portsmouth. It was purchased in 1834 by Thomas G. Gaylord, who within a few years had disposed his interests to Benjamin B. Gaylord, John P. Gould, and Abram Morrell under the management of the Thomas G. Gaylord & Company. 6 18 Production expanded to include boilerplates, sheet iron, bar iron, rivets, cut nails, and castings. A crucible steel facility and open-hearth furnace were soon added.

In 1869, the industrial site was leased to the Portsmouth Iron & Steel Company for nine years. 6 Gaylord was reorganized as the Gaylord Rolling Mill Company in 1872 and Ben Gaylord was named president and general manager. 18 Owing to the financial depression and the retirement of Gaylord, the plant was closed for several months in 1878 and subsequently leased to Portsmouth Iron & Steel (otherwise referred to as the Portsmouth Steel Company) in 1881.

Another mill, the Burgess Steel & Iron Works, named after Charles Burgess, 18 was established in 1871 at Third and Madison Street in Portsmouth with a capital stock of $150,000. 17 The plant had a capacity of 3,500 tons annually before expansion increased it to 50,000 tons. The mill burned on June 7, 1898, 9 17 which caused $250,000 in capital losses to the plant and $300,000 in unfilled contract losses, leaving 500 unemployed.

Burgess Steel & Iron opted to rebuild in the Yorktown addition of New Boston 2 6 19 where the president, Levi D. York, owned land. 9 19 The new facility included four 30-ton open-hearth furnaces, two 4-hole soaking pits, a 28-inch bloomer, two plate mills, twelve gas producers, twelve 100-HP dynamos, two 250-HP steam engines, and an 18-inch bar mill. 2 6 9 The massive steam engines were constructed by the Portsmouth Foundry & Machine Company. 9 Overhead electrical cranes were used to handle the hot metal and heavy machinery, a first for the steel industry.

By November 24, the rebuilt mill was rolling steel 9 and was in full operation by early 1899, producing 50,000 tons of steel annually with 700 workers. 9 19

Crucible Steel Company of America acquired Burgess Steel & Iron on July 15, 1900, 9 but the company folded on December 8 because it was having difficulties in obtaining raw materials. 20 The Whitaker Iron Works and Laughlin Nail Works acquired the closed plant in January 1902. 9 20 Soon after, the city of Portsmouth contributed $20,000 to the facility, which was reopened in June as the Portsmouth Steel Company. 2 6 9 It shipped its first carload of product to the Cleveland Rolling Mills on June 18, 1902.

A plate mill was added in 1905, followed by a blooming mill, five sheet mills, three jobbing mills, and sheet galvanizing lines in 1909-10. 21 A power plant was then added, followed by a steel bar mill in early 1914 and the dismantling of the plate mill in December. A coke plant was finished in 1916, followed by an 800-ton daily Old Susie blast furnace. 8

Portsmouth Steel joined with Whitaker Iron Works and Laughlin Nail Works to reorganize as the Whitaker-Glessner Company 9 on February 2, 1915. 21 On June 21, 1920,9 the Whitaker-Glessner Company, LaBelle Iron Works, and the Wheeling Steel and Iron Company combined to form the Wheeling Steel Corporation. Rod and wire mill divisions were added in 1921, followed by wire drawing equipment in 1923, additional sheet mills in 1924, and a new coke plant in 1930. 9

During World War II, Wheeling Steel manufactured some of the military’s largest orders of 250- and 500-lb. bombs and became the largest center of production for 500-lb. bombs. 7 After the fall of Germany, veterans of the war visited the plant to encourage the employees and to discourage absenteeism as the Pacific Theater was still ongoing.

Wheeling Steel sold its New Boston operations to a group of Ohio financiers in July 1946, and the plant was renamed the Portsmouth Steel Corporation. 9 The sheet mill was remodeled at the cost of $5.75 million in May 1948. By the end of the year, the factory was producing $49 million worth of steel annually with 3,800 employees.

Portsmouth Steel was sold to the Detroit Steel Corporation in 1950 who soon completed $150 million worth of expansions and modernizations to the facility, including a rebuilt coke plant in 1956 and a new $5 million central steam plant that utilized waste by-product gas from the adjacent coke plant and blast furnace. 2 6 9 10

Decline

Throughout the 1950s, total U.S. steel exports remained static, and the nation’s share of the world steel trade dropped from 53.6% in 1947 to 6.9% in 1960. 22 Most of the decline was the result of the decrease in post-war reconstruction in Japan and Europe. Instead of relying on domestic steel producers, local industrial firms imported increasing quantities of steel from abroad. Between 1950 and 1965, total U.S. imports of steel grew from 1,077 tons to 10,383 tons.

In 1969, Detroit Steel sold its New Boston plant to Cyclops Corporation, a Pittsburgh-based specialty steel producer. 9 Facing a glut of business in the industry, Cyclops began a gradual shutdown of the mill in 1972, culminating with the announcement on February 22, 1980, that steel production would cease by May 31, leaving 1,200 out of work. The coke plant would not be affected by the closure, although Cyclops intended to sell it to another interest to offset the steel mill’s losses.

The coke plant was sold to the McClouth Steel Corporation of Detroit in November 1980, which became known as the New Boston Coke Corporation, a unit of McClouth Steel. McClouth faced intense competition for its steel products and went into bankruptcy in November 1981. New Boston Coke divorced itself from McClouth and became an independent coke supplier.

Most of the former steelmaking facilities of Detroit Steel were demolished in 1989 for a new shopping center anchored by a Wal-Mart and a Buy-For-Less grocery store. 2

Coke Plant Closure

The Southern Ohio Port Authority (SOPA) removed 26,000 cubic yards of soil and waste materials that were contaminated with PCBs, asbestos, and petroleum from the former steel mill in 1997. It was followed up by the state Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) issuing a covenant not to sue SOPA for land that was remedied, which was vital for the sale of the property to OSCO Industries who had intended to construct a factory to produce castings for the appliance and automotive industries.

A test of coke oven gas that was emitted from New Boston Coke in June 1999 revealed high levels of benzene and butadiene, both carcinogens, in the local air. 4 The air quality in New Boston was considered worse than some of the largest industrial sites in the nation. 12 The state EPA filed a lawsuit against the company in December over violations of its air permits. 4 Separately, the state EPA ordered the company to clean up thousands of gallons of ammonia liquor and dispose of barrels of chemical waste.

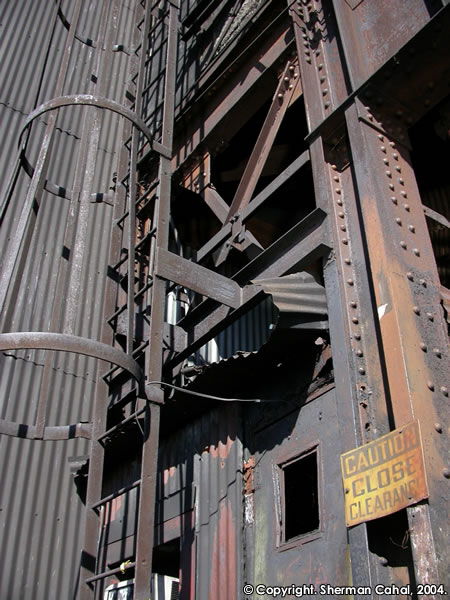

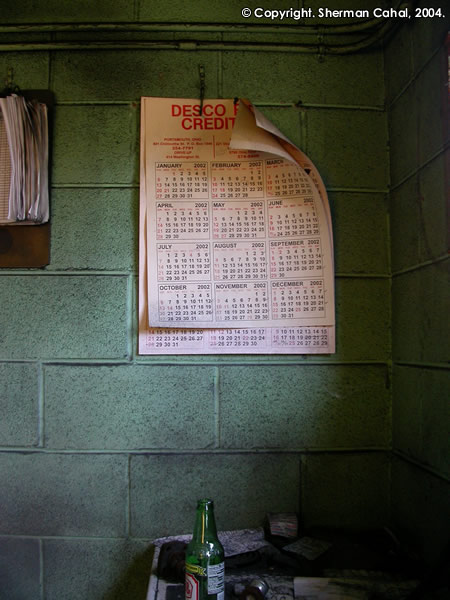

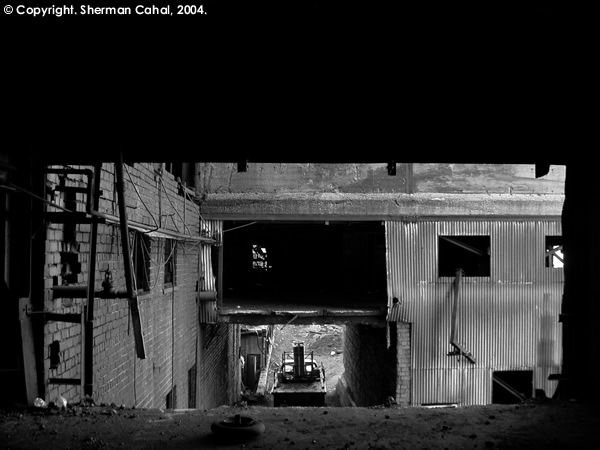

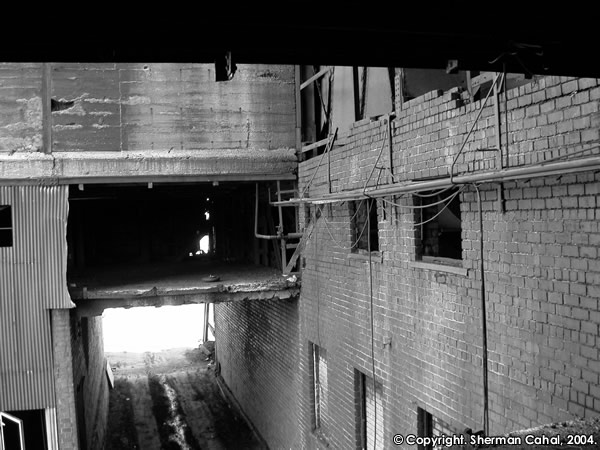

Facing a financial inability to add a permanent flare to incinerate all coke oven gas by the end of 1999, the coke plant was shut down in April 2002. 12 Approximately 200 jobs were eliminated. 13 In March 2007, Total Safety Inc. of South Point was awarded a contract for oversight of structural demolition of the coke plant, with the plant demolished over the course of the year. 11

Redevelopment

In the spring of 2004, Wal-Mart announced its intention to build a new store in front of the former New Boston Coke plant but work did not progress due to the extensive ground contamination at the site. The ground was broken for a new 210,000 square-foot supercenter on August 28, 2006, 16 which opened in June 2007. 12

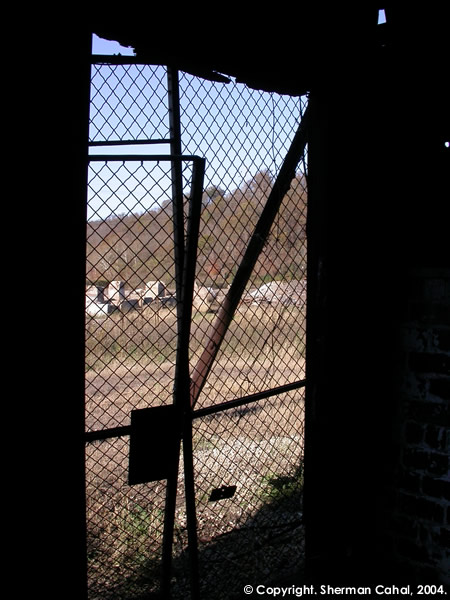

Gallery

Share

Sources

- “Inside Detroit Steel.” Detroit Steel Corp., Portsmouth Division Nov 1961 (V.11 #11 pp 7-8).

- Blackburn, Lori. Article.

- “Ohio Voluntary Action Program Annual Report.” Environmental Protection Agency. June 1997, Article.

- “State Takes Action.” Environmental Protection Agency. 2 December 1999, Article.

- “Settlement Reached.” Environmental Protection Agency. 28 September 2004, Article.

- New Boston Centennial Celebration 2006. Waverly: K&M Printing, 2006.

- McHelly, Lori. “New Boston was a munitions mecca during World War II.” New Boston Centennial Celebration 2006. pg. 18.

- “The Blast Furnace.” New Boston Centennial Celebration 2006. pg. 19.

- Jenkins, Steve. “Iron and Steel Industry in New Boston, Ohio.”

- “Portsmouth’s $5 Million Steam Plant Is Now Nearing Completion.”

- “Coke plant contract awarded.” Lawrence Herald (Huntington), March 15, 2007. March 17, 2007.

- Ottney, Ryan Scott. “New Boston Coke to be razed.” Portsmouth Daily Times, March 13, 2007. March 17, 2007 Article.

- Barron, Jeff. “Cleanup costs not known.” Portsmouth Daily Times, July 28, 2006. March 17, 2007 Article.

- Barron, Jeff. “Commission considers river port.” Portsmouth Daily Times, March 21, 2006. March 17, 2007 Article.

- Barron, Jeff. “City may buy coke plant land.” Portsmouth Daily Times, July 11, 2006. March 17, 2007 Article.

- Lewis, Frank. “Building phase nears.” Portsmouth Daily Times, August 29, 2006. March 17, 2007 Article.

- “Banks and Business: Burgess Steel and Iron Works.” A Standard History of the Hanging Rock Iron Region of Ohio. Ed. Eugene B. Willard et al. Vol. 1. 1916. Marceline, MO: Walsworth,, n.d. 219. Print.

- “Banks and Business: Gaylord Rolling Mill.” A Standard History of the Hanging Rock Iron Region of Ohio. Ed. Eugene B. Willard et al. Vol. 1. 1916. Marceline, MO: Walsworth,, n.d. 216-217. Print.

- “Banks and Business: Works Rebuilt at New Boston.” A Standard History of the Hanging Rock Iron Region of Ohio. Ed. Eugene B. Willard et al. Vol. 1. 1916. Marceline, MO: Walsworth,, n.d. 219-220. Print.

- “Banks and Business: Portsmouth Steel Company.” A Standard History of the Hanging Rock Iron Region of Ohio. Ed. Eugene B. Willard et al. Vol. 1. 1916. Marceline, MO: Walsworth,, n.d. 220. Print.

- “Banks and Business: Whittaker-Glesner Company.” A Standard History of the Hanging Rock Iron Region of Ohio. Ed. Eugene B. Willard et al. Vol. 1. 1916. Marceline, MO: Walsworth,, n.d. 220-221. Print.

- International Directory of Company Histories, Vol. 26. St. James Press, 1999.

5 Comments

Add Yours →New Boston just doesn’t smell the same anymore. 😉

I toured the plant with my father when I was a youngster. My dad was an employee at that mill for 33 years.He passed away in 1967/ two years short of retireing.

Believe it or not— this is one of the field trips we went on when I was in high school. It was really interesting. I graduated in 1960 so it was just b4 then!

All kinds of industrial places had tours back in the day! I miss that.

I am looking for information and pictures on General Electric 95 ton locomotives that you may have. An example of one of these is picture # 2 in Rail Shops section on the New Boston Coke article.

Thank you

Carson Wiebe